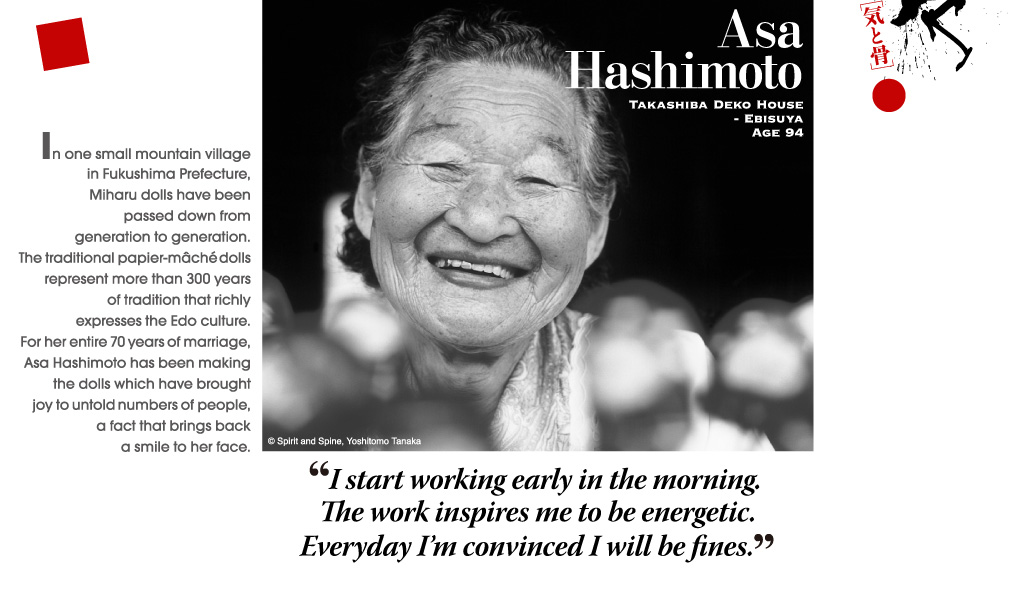

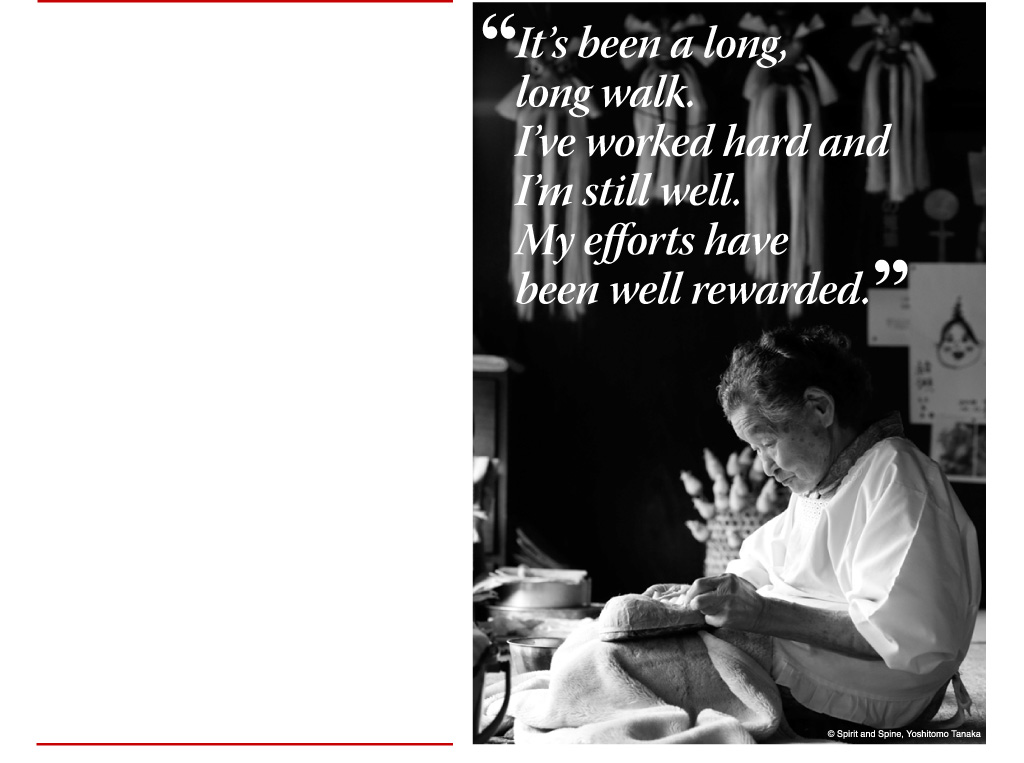

In a spacious tatami-mat room in the 200-year-old farm house, Asa Hashimoto sits demurely, uninterruptedly affixing Japanese paper to an old shiny black wooden mold. This process is crucial because it directly affects the finish of the dolls. Her lustrous hands and fingers appear big for her small body.

“Affixing paper has always been a job for wives. Use the paper with care,” she was told by her mother-in-law who never stopped working even though she was over 80. Asa has spent even more years than her mother-in-law dedicated to carrying on the traditional family business. She has been supporting her father-in-law, husband, and son who is the seventeenth master of the Hashimoto family.

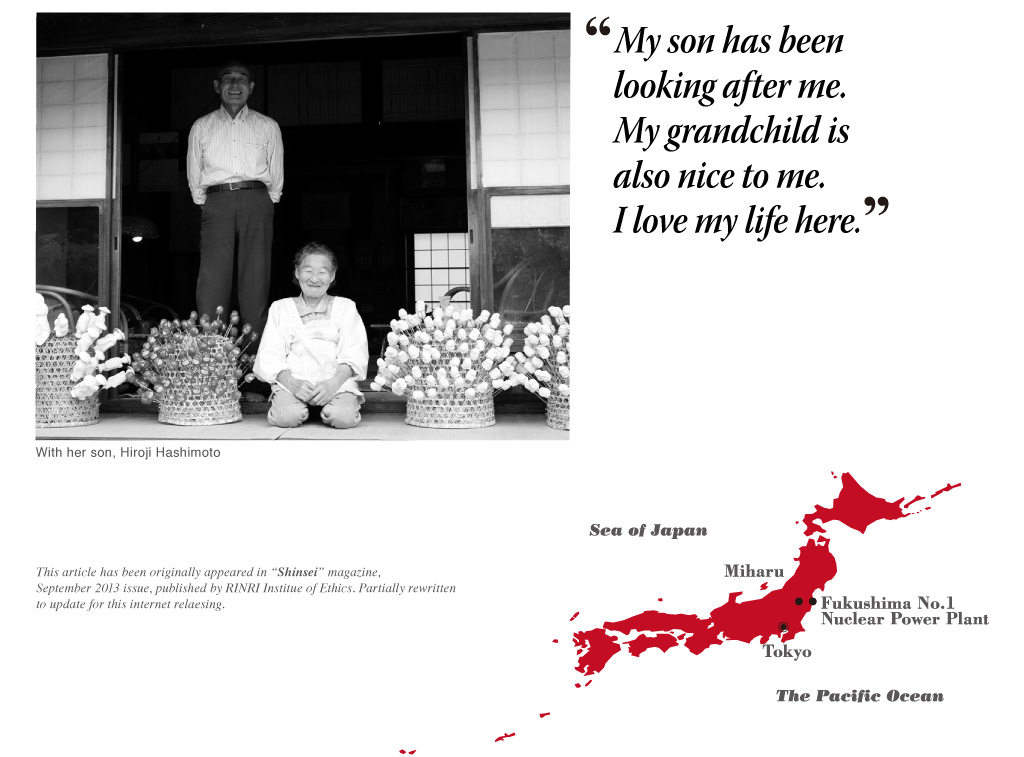

Although the Hashimoto family has been making dolls since the Edo period, farming was the family’s bread and butter when she first married into the family. She helped with the family’s sericulture business and worked on a farm. She even prepared meals for as many as 13 family members every day. Miharu dolls regained a reputation after the war due to the renaissance of folkcraft. Asa’s son has followed in the shoes of her husband who was active in product exhibitions around the country as a doll maker.

Although damage caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake was not significant for the village, still they have suffered as a result of the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. And the number of visitors has decreased dramatically, hurting sales. Despite that, the beautiful scenery of the lush green village flourishes, and the family continues undaunted, making dolls quietly, absorbed in the tradition.